An immigration story dodges conventions

Written by Annie Landenberger

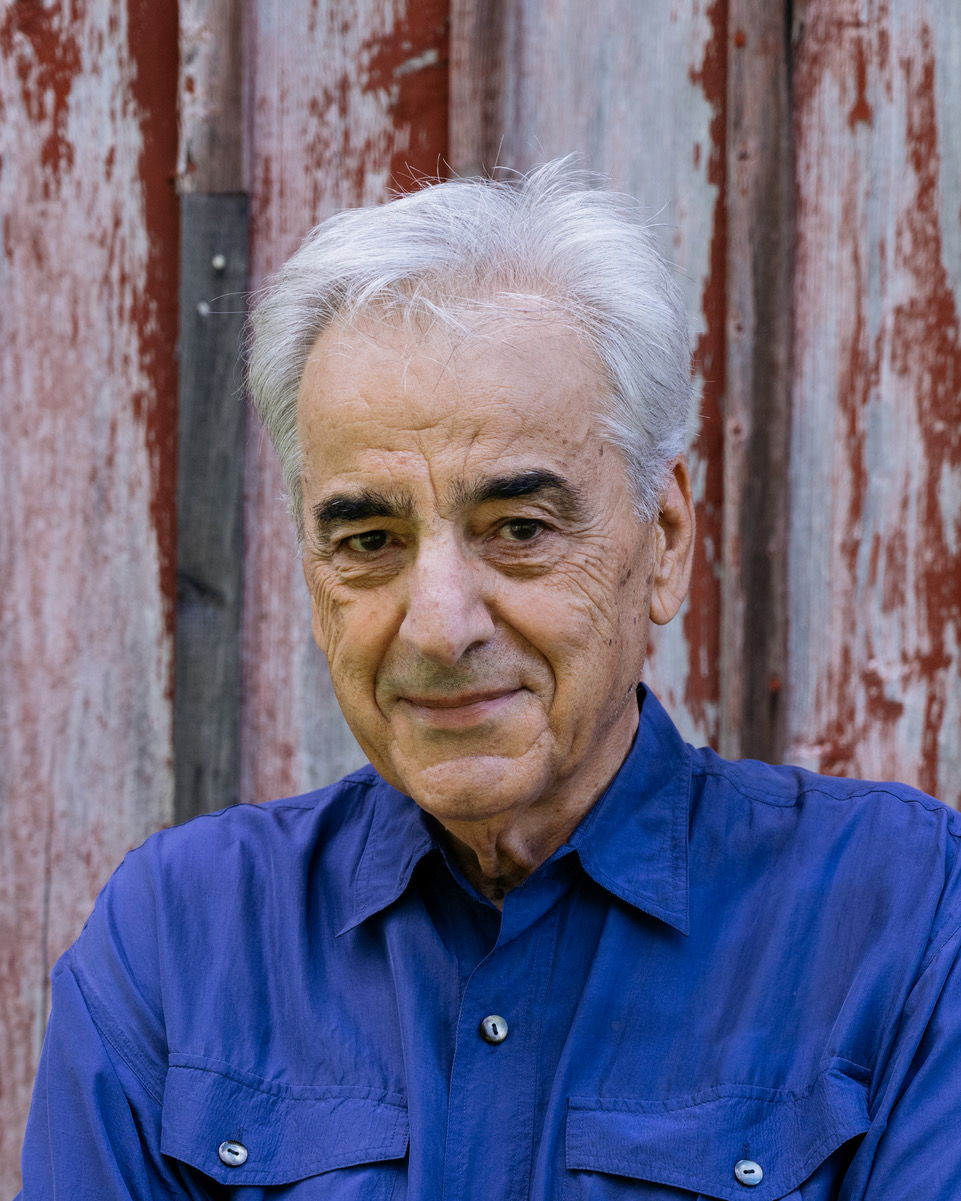

In his new novel, ‘Sicilian Dreams,’ Marlboro novelist Vincent Panella tells broad truths about his Italian American roots.

“He couldn’t take his children back home where the March winters blew on his house, where his dear mother swaddled like a child huddled near the warm bricks of the bread oven. This was how the old ones died in Castellano. Every winter took its toll, and the children would find the American money inside a wall. Going home would be like some reversal of an action, a comedy from a movie arcade where a man cranked a filmstrip the wrong way.”

—From Sicilian Dreams, by Vincent Panella

NEWFANE — IMAGINE THIS: In 1840, 37 immigrants came from Italy to the United States.

In 1907 — the year in which novelist Vincent Panella’s latest work, Sicilian Dreams, is set, 285,731 did so — the greatest number in history.

Such an explosion of dreamers was eager to reboot here in America, among them, Panella’s family.

Panella lives up on Augur Hole Road, just beyond the Marlboro border, in an 1840 home that she shares with his wife, photographer Susan Sichel. A vast sea of knowledge and experience lies between Panella’s studio on a dirt road in the country and the circumstances of Sicilian Dreams, published last fall.

A very personal immigrant narrative, Sicilian Dreams gives the reader a window into the desperation that can lead to corruption when the going gets just too tough.

The story follows 32-year-old Santo Regina, a common Sicilian laborer, recently widowed, with two children, Mariana, 16, and her younger brother, Franco.

A proponent of the Fasci, a popular democratic, socialist movement that emerged in late-19th-century Sicily, Santo boasts a workers’-rights activist’s streak which gets him into hot water both at home in Sicily and in L’America, as the Italian immigrant cohort calls it.

First landing in Louisiana, Santo leads the reader through experiences that are not too unlike those of enslaved African-American people on cotton plantations.

An eye-opener for this reader, at least, we learn that Sicilians were often not far behind enslaved Blacks in terms of degraded status and grave injustice suffered — including outrageous punishment, lynching included.

Despite exhausting setbacks, Santo perseveres.

Panella tells it all lucidly, vividly; his prose is, in turn, rough and raw, sweet and rich. He scooped me up from an armchair overlooking the Rock River and beamed me to the Sicilian countryside, at once beautiful and dreadful; to the fields of Louisiana, where many Sicilians landed before heading to New York City, and the streets of New Orleans; to the tenements, shops, and alleys of lower Manhattan; to steerage.

* * *

PANELLA BEGAN WRITING six decades ago at age 21. A graduate of Brooklyn Technical High School with a bachelor’s degree from Carnegie Mellon University in metallurgical engineering — he was the first in his family to go to college — he’d taken a job as a tech writer but soon felt called beyond that.

He fondly recalls a supportive grandmother who ordered silence whenever her grandson’s muse called so he could hole himself up to test the craft in the basement of the nuclear family’s tight Queens home. That nonna “was a strong lady,” Panella recalls — one who’d come through Ellis Island alone at age 17 and worked hard in New York to earn the security and acceptance so coveted by immigrants.

In the Queens home, Panella grew up with that grandmother, three sisters, and his parents. His mother was born in New York to a family from a small town outside Palermo.

They lived at the corner of 33rd and 10th, where her father ran a bakery, using wood collected by kids from the streets to fire the basement oven. Panella’s father, born near Naples in 1915, came here at age 6, a few years after his own mother had died of the Spanish Influenza.

First a New York City fireman, the senior Panella eventually owned and operated a string of bars.

Vincent Panella recalls the Marine Bar at 5 South St., way down by Battery Park and under sea level, where as a 10-year-old he would linger among crusty seamen and dock workers. The Marine Bar started flush, but when the piers were moved to New Jersey, it became a place where old guys would drink the sweet muscatel and spin stories that captured the young Panella’s ear and imagination.

This was a rough lot: “In the winter they’d wear sport coats and no shirts underneath,” he said. He recalls patrons ragging on each other, aiming to pick fights that, in the end, they’d be too weak and soused to carry through.

Panella’s father deliberately exposed him to this world. Though the bar business was his bread and butter, “he was against drinking in bars and saw those who did to be lonely and sick,” Panella recalls.

“He took me to bars to show me the evils of drink. He was intent on keeping me on the straight and narrow, making sure I stayed in high school.”

Panella’s father didn’t want to see his son run off and join the Navy, as many kids in the neighborhood did, but “I rebelled in my own ways,” he says.

His family then moved north to Newburgh, N.Y., where his father owned and ran another bar before moving to real estate.

Panella never went home after that.

“Family is hard,” he says. “Sometimes you have to avoid it.”

His relationship with his father seems as complicated as that of Mariana’s with Santo in Dreams.

* * *

AFTER COLLEGE, Panella enlisted in the Army for two years, after which he worked in failure analysis for missile programs (irony not intended). Soon fed up with the technological world, though, he earned a master’s degree from Penn State in English before scoring a place at the highly regarded Iowa Writers’ Workshop, earning a master of fine arts degree in 1971.

Studying under William Price Fox, he was right behind John Irving and in the same class as James Alan McPherson in the program that has given the world countless topnotch writers.

After Iowa, he took a reporting job at the Dubuque Telegraph Herald while he and Sichel lived in a bare-bones rented farmhouse. The rough days in an unwinterized home were eased by a stretch of six winters teaching composition at Florida State University College of Law. He did similar coaching more recently for 16 years at Vermont Law School.

Sichel had family in Vermont, so they moved here in 1976. The lives of their four children growing up in the country were, no doubt, radically different from Panella’s in Queens. His Jackson Heights neighborhood was Irish and Jewish; there weren’t too many kids like him on the block.

His father wouldn’t let him go to the local parochial school because “it was run by Irish.” As if the animosity between immigrant and sitting Americans hadn’t been enough, the animosity among various ethnic groups was palpable and volatile. He went to PS 69 instead.

“My family were the simplest of people,” Panella says, and so his characters are largely fictitious, steeped in historic accuracy.

Two of the characters we meet in Dreams — police officer Joe Petrosino and prominent mob boss Don Vito Cascio Ferro — are real-life extractions; the rest are, as Panella says, “concoctions.”

I asked about the novel’s women — many of whom are written with strong backbones and admirably bold. A few women whom Panella knew well growing up had rebelled against the constraints of their heavily patriarchal, hierarchical Italian families. And this we see in Santo’s daughter and her aunt Angelina, among others.

Unexpectedly, Panella gives us William, a Black immigrant from non-slave roots who serves as a sort of deus ex machina when the muck hits the fan for Santo in Louisiana and serves as the soul and the sine qua non of Santo’s reinvention on American soil.

* * *

PANELLA is a contributor to Vermont Views Magazine and has been published in an online Italian-American magazine, Ovunque Siamo (translation: Wherever We Are). One of his stories therein was a Pushcart Prize nominee.

Published by Bordighera Press, located at the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute in New York City, Sicilian Dreams has hit bookstores and book groups and is available at Everyone’s Books in Brattleboro and wherever books are sold.

As is the case with nearly every small press publication, Panella notes, “it’s tough to get [it] out there,” and the pandemic hasn’t helped promotion opportunities; nonetheless, he has been a guest of the Vermont Italian Cultural Association and other Italo-focused entities; moreover, he’s aiming to get the book into the hands of an Italian publisher for publication in translation.

Panella’s previous books include the memoir The Other Side: Growing Up Italian in America, the novel Cutter’s Island: Caesar in Captivity, and a short story collection, Lost Hearts.He’s finishing another collection of stories, Disorderly Conduct, and a novel.

His days are dedicated to his craft — reading and writing — and to staying well: walking, biking, shoveling snow, or working the raised beds in his vegetable garden.

* * *

PANELLA’S BEEN to Italy many times; he speaks “roughly functional” Italian, and he’s immersed in immigrant history. Thus, certain events alluded to in Sicilian Dreams are historical, and others certainly could have been.

“I did a lot of research,” Panella recalls, primarily at the Center for Migration Studies of New York. And that yielded access to some of the novel’s most unsettling moments.

Why so much violence? I wondered. Of course, looming high among all ethnic stereotypes are the mafiosi, and we see many who could be such in Panella’s narrative, though the Mafia per se is not a character in the story — refreshingly.

Panella conjectures that this behavior among Sicilians springs from the mediaeval feudal system and the days when owners of vast lands leaned on land managers who, in turn, leaned on — and abused, often violently — common folk such as our Santo.

The result, Panella explains, in and among these small towns deliberately isolated for protection, “is an evolved society of men prone to and used to violence. That’s where it came from — it was a socioeconomic development.”

“The ethnic novel genre is glutted; Italians are still trying to write about it and figure it out,” Panella notes.

But Sicilian Dreams dodges conventions and establishes a context which, while certainly familiar, digs deep into the humanity — and inhumanity — of one family’s impossible trajectory and eventual access to a modicum of relief under a banner of promise.