Vincent Panella

By Vincent Panella

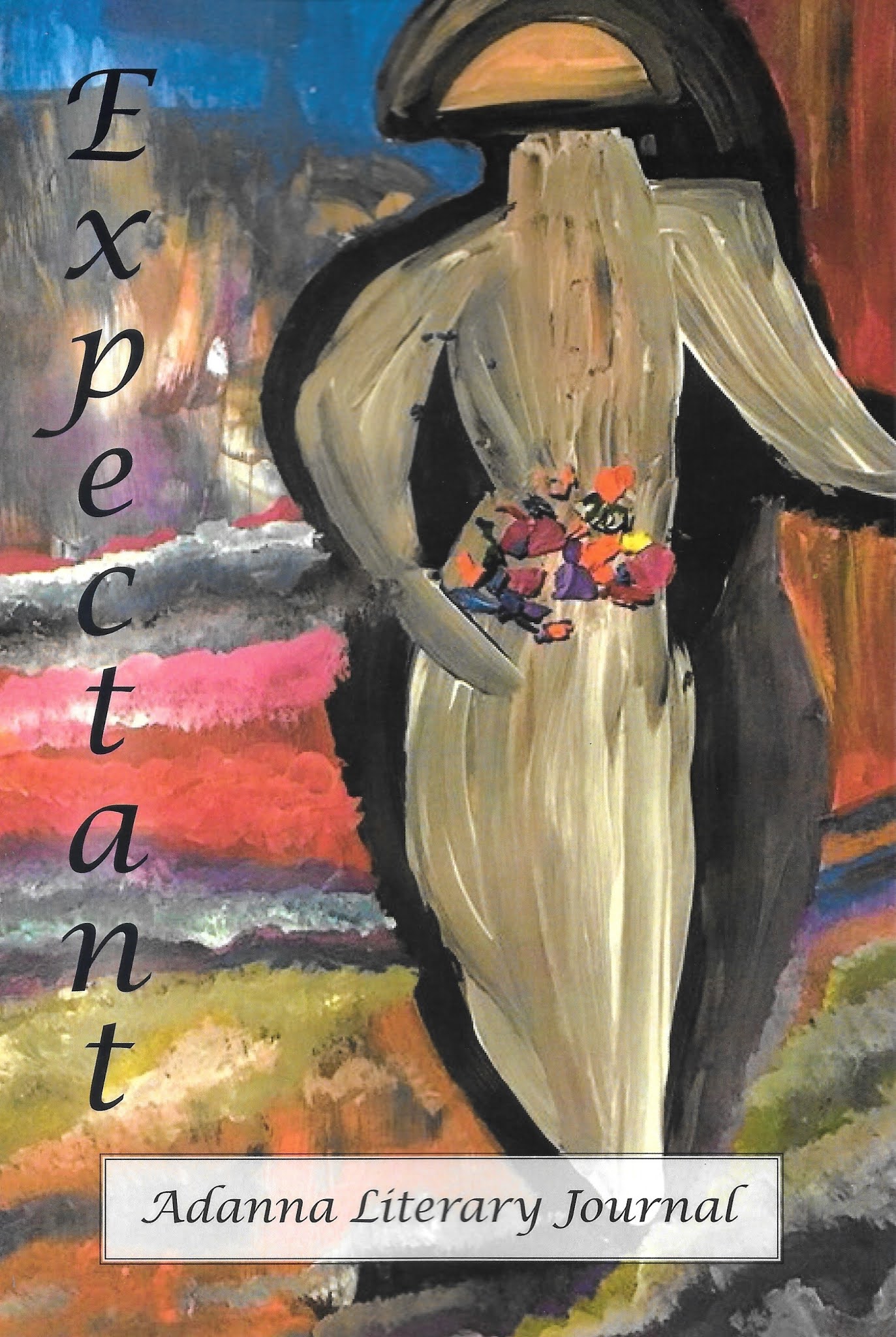

The Dress

A Story

I’m proud to have my short story, The Dress, included in a fine magazine open to the male perspective on the complex issues facing women today.

The Dress

By the virtue of last names, his Arlotti, and hers Atkins, their offices are adjacent and sequential, and this forces her to pass his open door on her way to work. Sometimes she brings her daughter, a six-year old with polio who walks with one foot dragging behind. When waiting for the daughter to catch up she stops within view, and since it’s the beginning of the school year and they barely know each other, their greetings are brief. She often wears an orange dress with white flowers, a dress he will fix in memory long after they separate. She’s older and he’s drawn to that, and when she passes by he studies the way her hips have narrowed and how the dress hangs with a touch of looseness suggesting a vulnerability that makes him want to protect her. When her students arrive for conferences he rises from his desk and puts his ear to the wall. With a growing desire he’s drawn to her lisping voice and flawless pronunciation and he sees in her a remedy for his loneliness.

He manages to sit next to her at meetings and she seems to like his jokes. He begins to visit her office with egregious passages from student themes. As his visits become more frequent they learn more about each other. She’s a single mother, and he’s recently separated and living alone, sharing custody of two children with his wife.

One day when she’s alone in the hall he asks why they can’t go out for a coffee or a beer. She fixes him through cat eye glasses, her eyes wet from reading.

“I have to pick up my kid and I’m late.”

Encouraged, he gives her his phone number and says he isn’t the type to push. He returns to his office which overlooks the parking lot where she tosses her brief case into a VW Beetle, starts the motor with a rumble from a bad muffler and pushes the gears to the limits. He watches until she’s out of sight.

A few nights later his phone rings and she says her parents have taken Bethany for the weekend.

“So will you buy me that beer?”

At a student bar he talks about the failure of his marriage and the difficulty of shared custody. She says, “What you’re going through isn’t easy, but at least you have a marriage to dissolve. ‘Mister Atkins’ said he could never have fathered a child with polio. He moved out of the country and now he’s unreachable.”

He asks her why she keeps the name of the man who fathered her child and refuses to support her.

“Is it less of an insult to bear his name rather than your own father’s?”

“Life is full of insults. One has to choose.”

“What was wrong with your father?”

“We lived on a farm and he wouldn’t let me have a dog.”

“I don’t believe that.”

“There are things I can’t tell you.”

After leaving the bar they drive out to his place, a fourteen-room farm house on a gravel road. Many of the rooms are crammed with old furniture as part of the landlord’s collection of antiques. While going through the rooms they find themselves in a small space that could be either a study or a closet. They’re close together and when she doesn’t move away they kiss, gently at first. When he tries for a harder kiss she bites his lip.

“Why did you do that?”

“Because you’re going to hurt me.”

“How do you know that?”

“You’ll see.”

He visits her at night when Bethany is asleep. She lives in graduate student housing, one of the military surplus huts known as The Barracks. She’s a PhD candidate in Linguistics and books are stacked in columns on the cushions of a cheap couch. She always greets him in a robe held closed at the neck and he smells the lotions used to protect her skin from the dry heat of a space heater.

One night he shows her how to make spaghetti with clam sauce using fresh garlic and canned clams. After the dinner Bethany dances in the living room to an old Beatles album. She pivots on her braced foot and spins with arms outspread and long hair flying.

“Mommy dance with me!”

“We’re talking now, Sweetie.”

“I’ll dance with you!” he offers.

“NO!” She goes to her room.

“She gets cranky when she’s tired, just like her mother.”

“No, she resents me, it’s understandable. It might help if we lived together. Look at all the room I have.”

“That’s not possible.”

“Why not?”

“It’s too complicated. You’re better off with a younger woman.”

“I don’t want a younger woman.”

“She’ll find you, don’t worry.”

She removes her glasses as the start of a story she’s about to tell. It will be about men who take advantage. These are her favorite stories and his too because they allow him to think of himself as better than the men she describes.

“My thesis advisor came into my office a few nights ago. There was nobody in the building. He said, ‘I just wrote thirty pages of my novel and I’m full of sexual energy.’”

“What then?”

“I told him to roll it back through the computer.”

“What was his reaction?”

“He told me to get another advisor.”

“Did you?”

“I quit the program.”

“What will you do now?”

“I don’t know. I’m writing now.”

“Will you show me what you’re working on?”

“Probably never.”

“Why not?”

“For the same reason I won’t tell you my age or my father’s last name.”

In her bedroom the mattress and box spring are now on the floor. They squeaked too much when mounted on the frame. A bulb on a lamp wire hangs above the pillow. He lights a candle melted into a saucer and they keep the door half-open so she can listen for Bethany. When they make love he uses the word love but she never returns it. He searches for the word beyond her pleasure but the word is hiding behind a door he can’t open.

“You never give me that word.”

“We take what we need.”

That summer he goes away to teach. He meets that younger woman she talked about but resists the temptation to sleep with her. The catholic in him decides to confess – thought and act being the same – and he writes her a letter to explain why he was tempted. He says, I wanted you to say that word but you never did. She doesn’t write back, and upon his return he visits her in The Barracks. They sit on opposite sides of the small living room. The stacks of books on the couch are gone and she hugs her knees to her chest as if to protect herself.

“I’m leaving town,” she says.

For decades his memory of the dress instead of fading becomes more vivid. The orange color deepens to burnt sienna. The white flowers become larger and he imagines them as hibiscus. He follows her online and discovers her father’s name, Visser. He finds an aerial view of the farm she grew up on. A high school yearbook shows her in a round-collared blouse buttoned to the neck. From the date he calculates that she’s fifteen years older.

An image search brings up a single photo. She’s standing with a group called Seattle Women Against the Iraq War. They hold a sign saying Not In Our Name. Some of the women hold umbrellas and she wears a white rain hat with the brim turned down all around. He reads the angry set of her mouth. Her hair, once down to her waist, is cut short. Her email address contains the word femme and she lists herself as a community activist. He finds discussion threads where she writes about social security, the environment, sexual equality, the homeless, the raft of government failures.

Through an interlibrary loan he finds her thesis, a collection of three stories called The Rapist in the Dressing Room. The stories place the same female character in situations where men try to dominate, in laundromats, offices, the dressing rooms of clothing stores, places where women are physically and psychologically trapped. In one of the stories her character lists the men who took advantage, not as individuals but as types — the pseudo-intellectual, the conceited artist, the narcissist and ego driven, and finally, “the Vermicelli and clam sauce man.”

The bitterness doesn’t surprise him. After all, he didn’t inherit a child with polio whose father wouldn’t support her, he didn’t have a thesis advisor who practiced sexual blackmail, he hadn’t suffered as a single mother with very little money, he didn’t have a lover who complained of his inadequacy. And if she couldn’t acknowledge the best of what they’d shared, at least he had the dress as a reminder.

He’s sixty years old when he takes a plane to Seattle. Why not? The Lyft car leaves him in the driveway of a small house with a lake in the distance. The car in the driveway is a late model SUV with a radar detector on the dashboard. He remembers how she baked bread to save money when she lived in The Barracks, kneading the dough roughly to pick up more flour with her cat eye glasses over her nose and her eyes leaking tears from reading too much. She baked the loaves in square pans, the kind of bread his family called “American.”

The door opens to the bones of her clavicle, to a field of liver spots and freckles, to a necklace of deep colored stones of different sizes strung on a silver chain. Her hair is short and combed upward all around. He waits for the recognition, studies her eyes, gray as his hair, gray as her hair. A few seconds seem like an hour. He searches for the most honest thing he can say, words that will preserve the best part of what they had.

“Maybe you don’t remember the dress….”

She shuts the door in his face.

Contact Vincent

vincentpanella9@gmail.com