DEMOLITION

Primo Levi’s Moments of Reprieve is a story collection based on his one-year stay in Auschwitz. The stories follow his other writings about the experience, and for those those who don’t know, Levi was an Italian Jew and trained chemist. In 1943 he joined a group of partisans in the Italian mountains and was captured and sent to Auschwitz to work at a factory camp. He used his bread rations to pay another prisoner for German lessons, and with his knowledge of the language and his background as a chemist he was assigned to a factory producing synthetic rubber for Hitler’s armies. He survived by avoiding hard labor and trading stolen materials from the factory for extra food. Auschwitz was liberated by the Russians in 1945 while Levi lay in the camp hospital with scarlet fever. The SS evacuated the camp as the Red Army approached, forcing all but the gravely ill on a long death march. Levi’s illness spared him this fate.

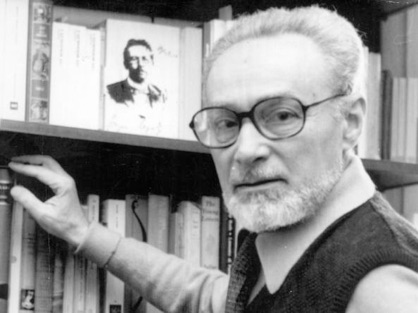

It would be another ten months in refugee camps before Levi returned to Italy. In later writings he noted the millions of displaced people on the roads and trains throughout Europe in that period. After his experience he wrote several books, novels, collections of short stories, essays, and poems. His best-known work is Survival in Auschwitz, an account of his year in the death camp and rightfully called a work of genius.

Moments of Reprieve is a collection of stories, vignettes, and character sketches, a tribute to moments when man’s better angels confront living hell. Levi’s characters are based on real people, some appearing in his other works, and some fictionalized from memory. He published the stories in 1981 after thinking he was finished writing about his experience, but the memories of people and their survival strategies – not always successful – compelled him to honor their lives. The characters whose stories demanded to be told were eventually given what Levi called “the ambiguous perennial existence of literary characters.”

With the logic of a scientist and the inspiration of an artist Levi sets his stories and characters against a background of horror. Hunger, beatings, and death are part of daily life. In these tales of survival a man sings few lines of opera to lighten a situation, the gift of a turnip is monumental, a half-slice of bread can be leveraged for favors. In one story Levi risks his life by writing a letter for another prisoner, his payment a ration of bread and a small pocket knife – itself worth five rations of bread. In another, a barracks chief saves the soup ration for a prisoner who asks permission to observe the Yom Kippur fast since eating is forbidden on the day of atonement. The barracks chief, a German ex-communist now cooperating with the Nazis, calls him meshuge, crazy. He is astounded that anyone would refuse a daily ration of watery soup. Later, perhaps from his own sense of guilt, the chief asks why anyone would make such a sacrifice. The prisoner, named Ezra, a Cantor from a small Lithuanian village, tries to explain atonement as a general concept, and when the chief asks about forgiveness for his own sins Ezra tactfully refers him to the Bible. The chief agrees to save the soup for Ezra’s next-day ration.

At the rubber factory Levi worked in a lab alongside non-prisoners with whom he was forbidden to speak words unrelated to work. One day a young German technician who appeared to like him asked – in whispers – if he could fix a flat on her bicycle. Levi considered this invitation to break the rules “potentially useful.” Having fixed the flat after a risky process of finding the tools, he was rewarded with a hard-boiled egg and four sugar cubes, a treasure trove for any prisoner. In telling the story Levi remarks, “One human German does not whitewash the innumerable or indifferent ones, but it does have the merit of breaking a stereotype.”

My own reaction to a visit to Auschwitz years ago was numbing. This was an industrialized death camp where over a million people were murdered, some shot, but most gassed and cremated. I passed under the infamous entry sign that said in German, Work Sets You Free. With other tourists I walked the cleanly swept streets in silence: how difficult to imagine or even speak about what happened here. What people, what sounds, who filled these streets at daily roll call, who sat behind desks in the broom-clean buildings, who gave the beatings and did the shooting at the Execution Wall? It’s all there, but it isn’t.

I entered the gas chamber and stared up at the nozzles which sprayed the Zyclon-B gas over those who thought they were getting a shower. I exited to the ovens and rail cars once packed with bodies. In an evidence building I stood in silence before glass fronted rooms containing belongings taken from the condemned: one room packed with pots and pans, another with boots and shoes, another with luggage, the leather dried and discolored with time, another filled with crutches, wooden limbs and assorted prosthetics, another with a mountain of hair shorn from the victims.

After the visit I rarely spoke about what I’d seen. I wrote almost nothing in my journals. On the few occasions when I mentioned that I’d been to Auschwitz and nearby Birkenau, I felt as if I was bragging, or revealing a terrible secret because to express what I’d seen would somehow profane the dead. What right did I have?

Our present circumstance frees me from this constraint. Does one so easily jump from death camps in Poland to our own conflicted country with its nearly 200 immigration/detention facilities usually located far from major cities where they attract minimal attention? The answer must be yes. Think of our prison system, one of the fastest growing industries. Think of how we maintain the largest immigration/detention infrastructure in the world, detaining hundreds of thousands per year. These include legal permanent residents with longstanding family and community ties, asylum-seekers, and victims of human trafficking – detained for weeks, months, and sometimes years in county jails and for-profit prisons.

So there is a parallel, and while those detained may may not be gassed or burned to ashes, other transgressions abound as their lives are taken away. Shortly after his arrival in Auschwitz, after his hair was shorn and his clothing surrendered, Levi stood naked in the snow clutching a bundle of rags and a pair of ill-fitting boots. This was the uniform he and others would wear. He wrote, “Then for the first time we became aware that our language lacks words to express this offense, the demolition of a man.”

Levi died in 1987 from injuries sustained in a fall from a third-story apartment landing. His death was officially ruled a suicide, but some have suggested the fall was accidental. He leaves one answer to our current state in this epitaph to Survival in Auschwitz:

You who live safe

In your warm houses,

You who find, returning in the evening,

Hot food and friendly faces:

Consider if this is a man

Who works in the mud

Who does not know peace

Who fights for a scrap of bread

Who dies because of a yes or a no.

Consider if this is a woman,

Without hair and without name

With no more strength to remember,

Her eyes empty and her womb cold

Like a frog in winter.

Meditate that this came about:

I commend these words to you.

Carve them in your hearts

At home, in the street,

Going to bed, rising;

Repeat them to your children,

Or may your house fall apart,

May illness impede you,

May your children turn their faces from you.

Recent Comments